Even while certain parasites are beneficial, they still require our protection in this ever-evolving environment; unfortunately, they do not appear to be receiving it.

In point of fact, researchers have documented a widespread extinction of marine species that are dependent for their survival on free-living hosts in the estuary that is the second largest in the United States.

According to the findings of researchers from the University of Washington (UW), the number of parasites identified in Puget Sound has decreased by 38% for every degree Celsius that the water’s surface temperature has increased over the previous 140 years, from 1880 to 2019.

The World’s Biggest Study On Parasites Has Found Something Terrible. They’re Dying.

While certain parasites may be harmful, most parasites in today’s fast evolving environment require our protection and don’t appear to be getting it.

Scientists have documented a massive extinction event among marine creatures in the United States’ second-largest estuary.

For every degree Celsius increase in sea surface temperature, the number of parasites in Puget Sound decreased by 38% over the 140 years from 1880 to 2019, according to study from the University of Washington (UW).

Researchers compiled the world’s largest and longest dataset on parasite abundance, and their findings are much more alarming than some conservationists had expected.

Parasites act as “invisible threads” that connect different nodes in food webs. Without their input, the health of ecosystems is unknown.

The results “are a huge bummer if you care about biodiversity or know anything about parasites,” UW parasitologist Chelsea Wood told ScienceAlert.

Even I was taken aback by the declines we saw.

Wood argues that similar losses in mammalian and avian populations would prompt quick conservation action.

For instance, between 1970 and 2017, bird populations in North America dropped by slightly more than 6 percent every decade, prompting significant attention to be paid to bird conservation.

Parasites, on the other hand, are largely ignored. It is often viewed as positive news that the number of parasitic animals is reducing. However, that is a narrow perspective that misses the forest for the trees.

Scientists now generally believe that global warming is leading to a sixth great extinction, and things look even worse when you consider how much of a role parasites play in maintaining Earth’s diverse array of life (the vast majority of which are undescribed).

Even though parasites play a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance, they are often ignored in ecological surveys and conservation efforts.

Our attention is typically drawn to parasites only when their numbers become problematic.

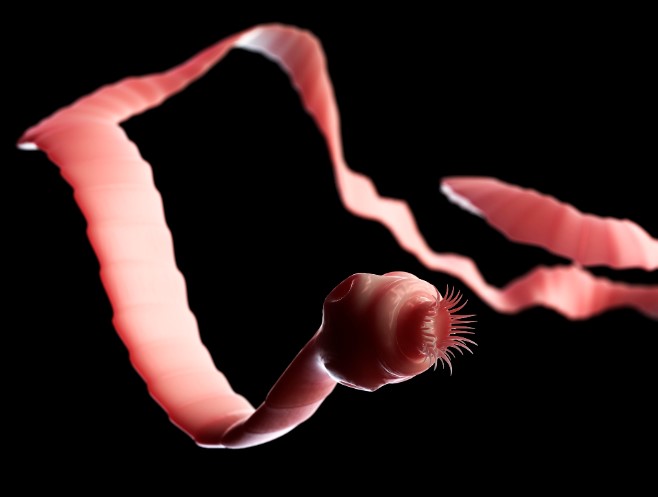

For example, a parasitic worm in raw seafood was found to have multiplied by a factor of 280 during the 1970s, a finding that made news in 2020 when it was discovered at Wood’s lab at UW.

Parasites generally aren’t doing so well, although certain species are doing quite well. It’s likely that the current climate crisis has already had a negative impact on many of them. They are vanishing quicker than we can count them, like bubbles in a pot of water.

Parasites that infect three or more hosts (about half of all parasites studied) appeared especially sensitive to warming waters in recent research out of Puget Sound.

As for the cause, rising seas may be affecting the availability and viability of the parasite’s host or hosts, or higher temperatures may pose a direct physiological risk to the parasites themselves.

A parasite’s vulnerability to climate change increases in proportion to the number of hosts it must switch between.

Also Read: Police Identified The Child Who Was Shot And Killed In Northeast Washington, DC

Nine of the ten parasites Wood found that were vanished by 1980 in Puget Sound had complex life cycles involving four or more hosts.

There will inevitably be winners and losers in any ecosystem that undergoes significant change, as Wood puts it.

However, we discovered far more failures in this place than we had bargained for.

Wood speculates that parasite losses in Puget Sound, like those in other ecosystems across the planet, could equal or even exceed the mass extinction rate among free-living species.

Although, unless additional studies replicate Wood’s findings, we won’t know for sure.

According to Wood, modern attitudes against parasites are analogous to those of the 1960s and 1970s toward apex predators like wolves and bears. Large carnivores were nearly exterminated by centuries of human hunting motivated by fear and resentment.

In fact, scientists didn’t figure out what had been done until the middle of the twentieth century. Habitats all throughout the world were suffering because some of the most crucial players in ecosystems were being methodically eradicated.

As it turns out, top predators weren’t always helpful pest controllers, but rather, they were crucial in maintaining stable ecosystems. The natural order of ecosystems was restored after their return to their former homes.

“That’s where we are now with parasites, Wood says. “We’re at this point when information is beginning to pile suggesting how awesomely strong parasites are in an ecosystem. There have been no leaks of this material to the general public as of yet.”

A 2017 research of 457 parasite species estimated that as much as 10%, including 30% of parasitic worms, might go extinct by 2070. The findings prompted the authors to compile the first ever “red list” of threatened parasites.

To ensure the survival of parasites in the future, Wood and other like-minded scientists from around the world collaborated in 2020 to outline a 12-point strategy.

A co-author of the article, Colin Carlson, told The Atlantic in 2015 that we should cease killing parasites as soon as we find them.

‘The most fundamental principle, and it’s a bit absurd that we’ve missed this, is you don’t kill something if it’s doing okay,’ Carlson told reporter Ed Yong.

Also Read: A Twenty-Year-Old Man Was Found Dead Outside Of The Navy Yard Metro Station

Currently, Wood is ahead of the curve in data collection and synthesis. The research group she heads at the University of Washington is the first to use fish specimens from museums to construct a parasite prevalence chart for the oceans.

Wood claims that, to his knowledge, nobody other has seen this. “And it helps that nobody is observing.”

Parasites, unlike top-level predators, are more difficult to spot if you aren’t looking for them. Finding them is not a glitzy occupation.

Wood comments, “Your fieldwork is sitting in the basement of a museum, dissecting fish that are filled with terrible toxins.”

“There is nothing sexual about it. But it allows us to go back in time. And if I ever get the chance to go back in time, I’m going to take a whiff of formalin.”

There are historical and contemporary parasites for us to tally. We might as well just hold our breaths and jump in at this point.

Final Words

Although some parasites may provide some benefits, they still need our help adapting to the modern world, and they don’t seem to be getting it.

Specifically, scientists have found evidence of widespread extinction of marine species that rely on free-living hosts in the second-largest estuary in the United States.

For every degree Celsius that the water’s surface temperature has increased from 1880 to 2019, the number of parasites found in Puget Sound has fallen by 38%, according to study from the University of Washington (UW).